top of page

Lesson study cycle 1

How do we get students excited to explore our history, and in a way that ensures each student sees themself in the content we engage with? This is the question that guides my teaching philosophy. I am a lifelong learner always looking for new ways to ignite a sense of curiosity in the minds of my students.I believe that it is essential to spark students' curiosity to explore the world beyond the classroom, and to help them hone the skills they will need in college and beyond. Our world has become smaller and more interconnected than at any point in our collective history. Students have the vast wealth of human knowledge at their disposal; literally at their fingertips. Amazing as that may sound, many students will need guidance to safely navigate the expansive sea of information that lays before them.

In our first lesson study cycle we turned our attention to honing students writing abilities; specifically their ability two write evidence based paragraphs. We noticed that while students may be able to write and articulate their thoughts in a free flowing or stream of consciousness style of writing, they struggled when tasked with writing an academic paragraph. Our group decided to focus on assisting students in developing their academic writing ability through the introduction of a Claim-Evidence-Reasoning paragraph structure.

The Research

Over the course of this research cycle we have worked to identify ways that we can better support student acquisition of evidence based writing skills. We began by introducing students to a standard paragraph format for this type of writing (Claim/Evidence/Reason/ Evidence/ Reason/Connection). The focus then shifted to strengthening their ability to identify and utilize evidence, to not just support their claim, but also make inferences and learn how to “read between the lines.” While further exploring our team’s “research theme,” I came across Nadia Behizadeh’s “Realizing Powerful Writing Pedagogy in U.S. Public Schools,” in which they were critical of the writing instruction often utilized in U.S. public schools. According to the research compiled in Behizadeh’s article, “Writing instruction in the United States tends to focus on short, formulaic assignments that do not require criticality or connect to real-world events (Behizadeh, N., 2019, p. 261).” Upon reading this, I immediately wondered if our own attempts at developing students’ evidence based writing abilities could be considered “short, formulaic assignments?”

The article goes on to identify a powerful writing pedagogy (PWP) as a way to remedy the shortcomings of common writing instruction practices. The author defines PWP as a set of practices that center three essential elements: evidence based practices, methods for increased authenticity, and critical composition pedagogy. Another thing Behizadeh’s research highlights is the failure of writing instruction in preparing students to navigate sociopolitical issues in their writing. While this was not a focus of our group’s research, the application of evidence based writing techniques to politically charged argumentative writing and other genres is essential for students to grasp. Behizadeh argues that “students deserve access to writing instruction that helps them write to pass tests, meet standards, and write for the world and themselves (Behizadeh, N., 2019, p. 265).”

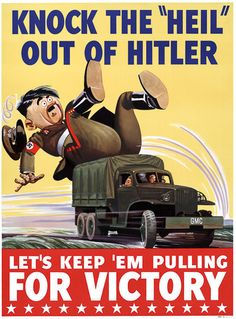

As we prepared to launch our series of lessons, I wondered how we could best ensure that our own lesson meets these PWP standards? Students examined propaganda from WWI and WWII in our lesson, so I wondered how we could ensure that we create opportunities for students to engage with the content in an authentic way. That also give them a chance to practice application of the evidence based writing skills we had been working on thus far. In their article, “Looking at World War I Propaganda,” Chris Sperry provides guidance on ensuring authentic interactions between students and source through the use of a constructivist media decoding approach. According to Sperry, “[students] growing cognitive abilities enable them to separate their perspectives from the views of their parents, school, peers, and society— to challenge themselves to figure out ‘What do I believe?’” (Sperry, C., 2014, p. 235).They go on to propose that media decoding helps to drive this truth-seeking behavior. The use of familiar strategies and practices in the classroom to facilitate media decoding sessions will make it that much more effective. In my own classroom we have gotten into the practice of doing weekly inference training using the the New York Times’ weekly “What’s Going On?” photo. This has gotten students familiar looking at media and making inferences by examining the evidence present in the image and by sharing thoughts and questions with peers. By utilizing a familiar practice in our upcoming lesson we can reduce student confusion. This will allow for greater focus on ensuring we incorporate the three essential elements of a PWP in our lesson.

knowing your Students

Focus Student "C"

This student is outspoken and not shy about sharing their thoughts with the class. However, they tend to avoid completing assigned tasks until the last possible minute. Additionally, they are working to improve their basic writing mechanics.

Focus Student "P"

This student tends to be quieter during class discussions. They expressed a desire to work on improving their writing over the course of this school year.

Focus Student "Z"

This student excels socially, but is still working to develop their academic preparedness. However, they tend to be task avoidant and require frequent reminders to stay on task.

implementation

Our Research lesson took place in a 10th Grade World History classroom, and was part of a unit on the World Wars. Over the course of this week long study of Propaganda and the role that it played in influencing public opinion during the World Wars. To understand the effects of propaganda students needed to acquire and understanding of bias, and how their own effects their perception of the world around them. Students spent the week leading up to the research lesson exploring common themes in propaganda, including women in war, the war on the home front, espionage, enlistment, and countries individual views and agendas.

Essential Questions

What is bias?

What is propaganda?

What do you believe?

Unit Lesson Plan

Day 1:

-

Lesson Goal: Understanding and identifying bias through inferences.

-

Task: Analyzing propaganda and identifying where positionalities introduce bias.

Day 2

-

Lesson Goal: Understand the historical context of the propaganda and identify whether it fits your previous understanding/first impressions (Were your inferences correct?)

-

Task: Analyzing primary and secondary sources to identify the correct historical narrative.

Day 3

-

Lesson Goal: Students will synthesize their understanding of the historical sources presented to them in lesson 2 by writing CER paragraphs.

-

Task: Student will write in response to the prompts: What is the correct historical narrative about the topic you chose? What is the propagandized narrative about the topic? How do the two narratives differ? What biases can you identify?

Day 4

-

Lesson Goal: Students will synthesize their understanding of the historical sources presented to them in lesson 2 by creating an infographic to display the information and how it informs what they believe.

-

Task: Students will use their own words to explain narratives told by the propaganda and the historical sources from the previous lesson;as they begin to draft portions of their final “Explodation” essays.

Day 5 (Research Lesson)

-

Lesson Goal: Students will write evidence based paragraphs that analyze how propaganda shapes national identities using inferences to deepen the analysis present in their writing.

-

Task: Students will write three OCIE paragraphs demonstrating their understanding of the bias present in propaganda, the accurate historical narrative and their own beliefs.

Student work

Students were tasked with using the information that you compiled over their week-long exploration of propaganda and the historical narrative to write a Claim-Evidence-Reasoning paragraph. Additionally they were tasked with pairing visual elements with their most powerful claims and evidence, turning their writing into an Explodation Paragraph. In this Explodation they must make a claim asserting what they believe about the specific propaganda topic examined this week. Most importantly, they must support their claim with evidence.

Guiding Questions:

-

What do you believe?

-

What does the propaganda communicate? What is the story it is telling?

-

What is the accurate historical narrative?

-

Did you identify any bias?

bottom of page